Turkey Vulture

- Scientific Name

- Cathartes aura

- Also Known As

- Turkey Buzzard, Buzzard

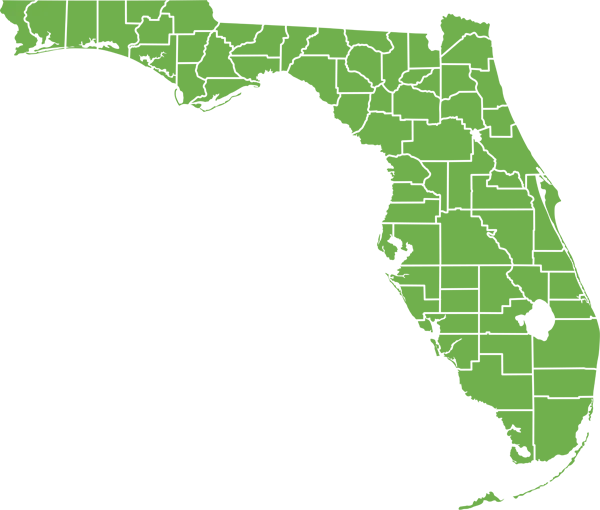

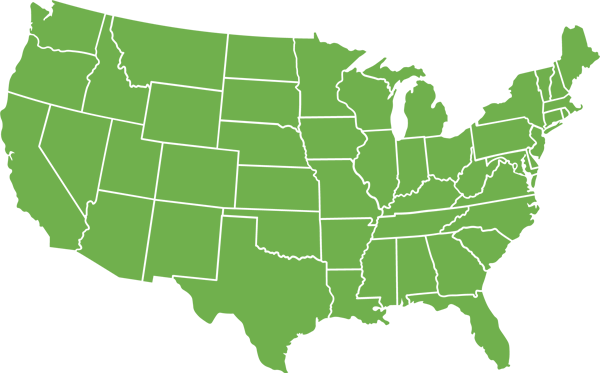

- Range

- All of Florida

- Diet

- Carrion

- Life Expectancy

- 16 Years

Quick Links

Turkey Vultures in Central Florida

The turkey vulture (Cathartes aura) is a common vulture species found throughout Florida, including the central region of the state. Sometimes called a turkey buzzard, this widespread scavenging bird plays an important role in the ecosystem. This guide provides tips on identifying turkey vultures, details on their biology and behavior, potential health risks, and exclusion methods to humanely prevent conflicts with these unique birds.

Appearance and Identification

Turkey vultures can be identified by their distinct physical characteristics

Turkey vultures can be distinguished from black vultures by their larger size, red head, silvery wing linings, and pronounced dihedral soaring profile.

Maturation Rate

Turkey vulture chicks grow rapidly, reaching adult mass in about 2.5 months after hatching. They depend on the parents for food and care during the first few months after fledging. Juveniles start scavenging independently at about 3 to 4 months old.

Habits and Behavior

Turkey vultures are diurnal and gregarious, roosting colonially at night. They soar on thermals during the day, using their keen sense of smell to locate carcasses. Turkey vultures are very social, even when feeding, and migrate in large flocks. They hiss, grunt, and regurgitate when disturbed. Turkey vultures lack a syrinx voice box, so they do not vocalize beyond hisses and grunts.

Reproduction and Lifespan

Turkey vultures reach sexual maturity at 2 to 3 years old. They mate for life, beginning courtship rituals like aerial displays in early spring. Nests are made in caves, hollow logs, and abandoned buildings. Females lay 1 to 3 eggs from March to June, which incubate for 28 to 40 days. The semialtricial hatchlings fledge in 10 to 11 weeks. Turkey vultures can live over 16 years in the wild.

Ideal Habitat and Range

The warm, subtropical climate of central Florida provides ideal habitat for turkey vultures. Mild winters with average lows around 60°F (15°C) allow year-round residence. Summer highs average in the low 90s°F (low 30s°C). Rainfall exceeds 50 inches annually.

Lush vegetation, wetlands, highways, and urban centers provide plentiful food sources for scavenging. Turkey vultures roost communally in tall trees, dead snags, and secluded buildings. Central Florida’s consistent warmth, abundant food, and roost sites allow stable, substantial turkey vulture populations.

Diet and Feeding

Turkey vultures are obligate scavengers, feeding exclusively on carrion. Using their keen sense of smell, turkey vultures locate and consume carcasses of large and small mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish, and invertebrates. They prefer fresh carcasses and avoid decayed remains. Turkey vultures have very low gastric pH, allowing them to digest rotten meat other animals couldn’t tolerate.

They do not regurgitate excessively acidic stomach contents like other vultures. Turkey vultures are important ecological clean-up crews, quickly locating and consuming carcasses before they can decay and spread bacteria.

Photo 13510464 © Dana Adobe Nipomo Amigos, Inc., CC BY-NC

Common Health Risks

While turkey vultures provide an invaluable service by consuming carrion that could otherwise spread disease, they can potentially transmit some pathogens and parasites to humans and livestock:

- Histoplasmosis – This lung infection is caused by inhaling spores of the fungus Histoplasma capsulatum, which grows in accumulations of bird and bat droppings. Disturbing vulture roosts releases fungal spores.

- Bacterial infections – Turkey vultures harbor bacteria like Salmonella, Escherichia coli, and Campylobacter on their feathers, feet, and beaks from consuming carcasses. These bacteria can contaminate surfaces.

- Parasitic infections – Roosting vultures may harbor external parasites like lice, fleas, and ticks that can spread diseases like tularemia, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and Lyme disease.

- Abrasions – The sharp talons and hooked beak of turkey vultures can inflict minor scratches and wounds if handled.

While turkey vultures generally avoid contact with living animals and humans, their droppings, feathers, and potential ectoparasites can pose health risks. Protective clothing, respiratory protection, and other precautions should be used when handling turkey vultures or cleaning roosting areas to prevent disease transmission. Promptly disinfecting surfaces contaminated by vultures is also crucial. With proper sanitation measures, the public health hazards associated with turkey vultures can be minimized.

Deterring Turkey Vultures

Several methods can be used to humanely deter turkey vultures from problematic roosting areas:

- Habitat modification – Remove tall trees and shrubs near buildings. Install roof spike strips or shock track

- Reflective deterrents – Mylar tape, balloons, and predator decoys.

- Sound and light devices – Motion-activated sprinklers, laser lights, loud music.

- Odor repellents – Ammonia, moth balls, predator urine. Avoid harmful chemicals.

- Population management – Seek permits for egg oiling, nest disruption, or live trapping and relocation as last resorts.

An integrated wildlife control approach customized for the situation works best for humane, legal turkey vulture deterrence.

Turkey Vultures in Central Florida – Conclusion

Turkey vultures are unique scavenging birds that provide vital ecosystem services in central Florida. Their adaptation to urbanization brings some conflicts with humans that require sustainable management solutions.

Through an understanding of turkey vulture biology and behavior, plus judicious habitat modification and exclusion techniques, these protected birds can be safely, humanely deterred from areas where they pose problems. With informed prevention and control methods, turkey vultures and humans can coexist for mutual benefit.