Nine Banded Armadillo

- Scientific Name

- Dasypus novemcinctus

- Also Known As

- Armored Pig, Hoover Hog

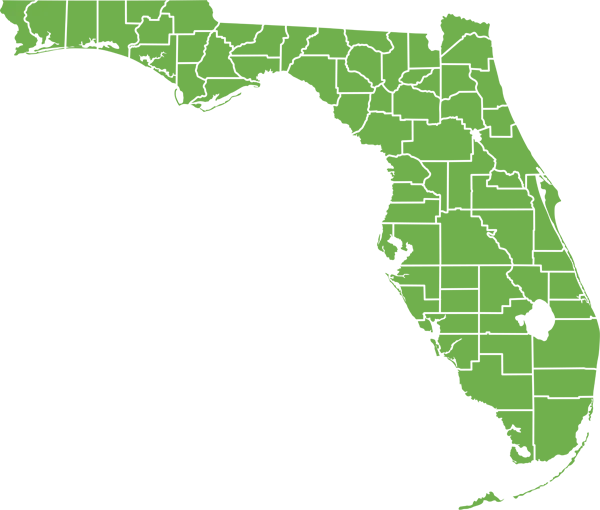

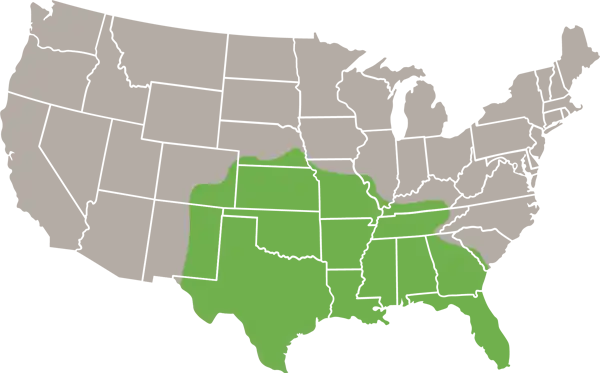

- Range

- All of Florida

- Diet

- Grubs, Beetles, Ants, Termites

- Life Expectancy

- 5 - 7 Years

Quick Links

Green Iguanas in Central Florida

The nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus) is a unique, armored mammal found throughout central Florida. Often seen rooting along roadsides or foraging in yards, armadillos are one of the more familiar exotic species in the region. This guide covers key identification features, biology, impacts, and control methods for nine-banded armadillos in central Florida.

Appearance and Identification

Nine-banded armadillos can be identified by their bony, armor-like shell and distinctively long, tapering snout.

Maturation Rate

The bony shell takes 8-10 weeks to fully harden after birth. Sexual maturity is reached by one year old. Adults continue growing until age three when they reach their maximum size.

Habits and Behavior

Armadillos are solitary, nocturnal omnivores. They spend the day in self-dug burrows or brushy areas, emerging at dusk to forage. Coastal populations may be more crepuscular or diurnal to avoid hot inland daytime temperatures.

Armadillos shuffle along slowly while foraging but can sprint, jump, and swim when startled. Their armor helps defend against predators like bobcats, coyotes, and free-roaming dogs. If threatened, armadillos may react by leaping straight into the air, grunting loudly, or shuffling away rapidly.

Nine-banded armadillos marking and burrowing habits can damage lawns, gardens, tree roots, and building foundations. Their constant rooting for grubs and insects aerates and disturbs soil. Burrows are used for sleeping, rearing young, and escape from extreme heat or cold.

Reproduction and Lifespan

The breeding season for nine-banded armadillos in Florida is July through August. After a gestation of 60-120 days, the female gives birth to genetically identical quadruplets from one fertilized egg. This is because armadillos have an unusual reproductive strategy called polyembryony, where a single fertilized egg splits into four embryos.

Newborns weigh just 3-4 oz (85-113 g) at birth. Young stay in the burrow for 2-3 weeks, then begin following their mother while foraging. They are weaned by 4 months old but remain close to the mother until the following mating season when they disperse to establish their own range.

In the wild, armadillos live up to 12 years. Predators, hunting, road mortality, and extreme cold limit average lifespan to just 5-7 years in cooler parts of their range. The warmer climate of central Florida allows higher survival.

Ideal Habitat and Range

Central Florida’s humid, subtropical climate provides excellent habitat for armadillos year-round. Average temperatures range from the 60s°F (16°C) in January to the 80s°F (27°C) in July. Rainfall exceeds 50 inches annually, especially during the summer wet season.

These warm, humid conditions allow dense vegetation like palmetto scrub, pine flatwoods, and swamps where armadillos thrive. Rural areas bordering suburbs and cities provide food and shelter. Armadillos are adaptable and utilize yards, parks, golf courses, cemeteries, and other modified habitats.

Their low metabolic rate allows them to survive cold snaps by decreasing their body temperature and remaining dormant in burrows. Due to lack of fat insulation, prolonged freezes can still be lethal. But their tolerance for heat and humidity allows armadillos to prosper across the Florida peninsula.

Diet and Feeding

Armadillos are omnivores with over 90% of their diet consisting of invertebrates. They forage by rooting through soil and leaf litter for grubs, beetles, ants, termites, and other insects. They also opportunistically eat amphibians, reptile eggs, carrion, fungi, fruits, seeds, and tender plant roots.

Armadillos detect prey using their excellent sense of smell. Their long, sticky tongue adheres to ants, grubs, and other invertebrates when probing underground. Powerful front claws allow them to quickly dig into ant mounds or soft soil in search of food.

Foraging occurs mostly at night but may expand into crepuscular and daytime hours in coastal areas. Armadillos are noted for their frequent roadside foraging which makes them highly susceptible to being struck by vehicles.

Photo 135020912 © Markham Park, CC BY-NC

Common Health Risks

Armadillos host several diseases that can infect humans through direct contact or inhalation of soil contaminated with armadillo feces:

- Leprosy – Caused by Mycobacterium leprae bacteria. Can be contracted by handling infected armadillos. Causes nerve damage, skin lesions, muscle weakness.

- Salmonellosis – Caused by Salmonella bacteria in feces. Causes diarrhea, vomiting, fever, cramps. Spread by contact or consuming contaminated water/food.

- Chagas disease – Caused by Trypanosoma cruzi parasite in feces. Causes fever, enlarged lymph nodes, heart damage.

Armadillos also commonly carry rabies, tularemia, and toxoplasmosis which are transmittable to domestic pets and humans. Use gloves and take precautions when handling or preparing armadillo meat. Cook thoroughly. Carefully dispose of carcasses, disinfect any soil contacted, and wash hands thoroughly afterwards.

Preventing Black Spiny-tailed Iguanas

- Clear brush, compost piles, and debris that provide shelter.

- Fill in burrows and holes. Use mesh fencing to prevent digging under sheds and foundations.

- Protect gardens with fences buried 6-12 inches (15-30 cm) underground. Electric fencing also deters entry.

- Seal foundation gaps and openings wider than 1/4 inch (6 mm) to exclude armadillos.

- Use pest-resistant plantings like aloe vera and junipers that deter grub populations.

- Use repellents like dried blood meal or milorganite fertilizer on lawns.

- Trap and remove armadillos that repeatedly invade yards. Check local regulations first.

Black Spiny-tailed Iguanas in Central Florida – Conclusion

The adaptability of the nine-banded armadillo allows it to thrive across diverse habitats in central Florida including suburbs, parks, farms, and natural ecosystems. Their rooting and burrowing behaviors can damage property, while also posing some health risks from transmission of diseases like leprosy and salmonellosis. Preventing access, reducing grub populations, and trapping persistent invaders helps protect landscapes from destructive armadillo activity. While armadillos are interesting creatures, their impacts show why management and control is often needed, especially in developed areas.